Lemon by Orlando Wood: Review

Introduction

Orlando Wood's book Lemon, which is published with the IPA (the Institute of Practitioners of Advertisers) and Effworks, is a hugely impressive work that will sit alongside How Brands Grow and The Long and The Short of It, as a piece of work that understands the value and traits of effective advertising. In his address to the Marketing Institute he brought together the art of the late-Roman period and advertising to show how human cognition has not changed that much, though we like to think it has.

His work focuses on the difference between the left side of the brain and the right side of the brain. I thought that this idea of left-brain/right-brain has been dismissed as pop psychology but Wood draws on the painstaking work of Iain McGilchrist to show that how we think about this concept has been wrong. Thinking about it correctly can give us a new insight into what makes effective advertising.

The overall message of this book is to be mindful of one style of thinking becoming overly dominant. Orlando argues that left-brain thinking has become the dominant style of thinking and as a result the creativity of the advertising world is in crisis. Without right-brain thinking we lose context, connection and other elements that create effective advertising.

Crisis of Effectiveness

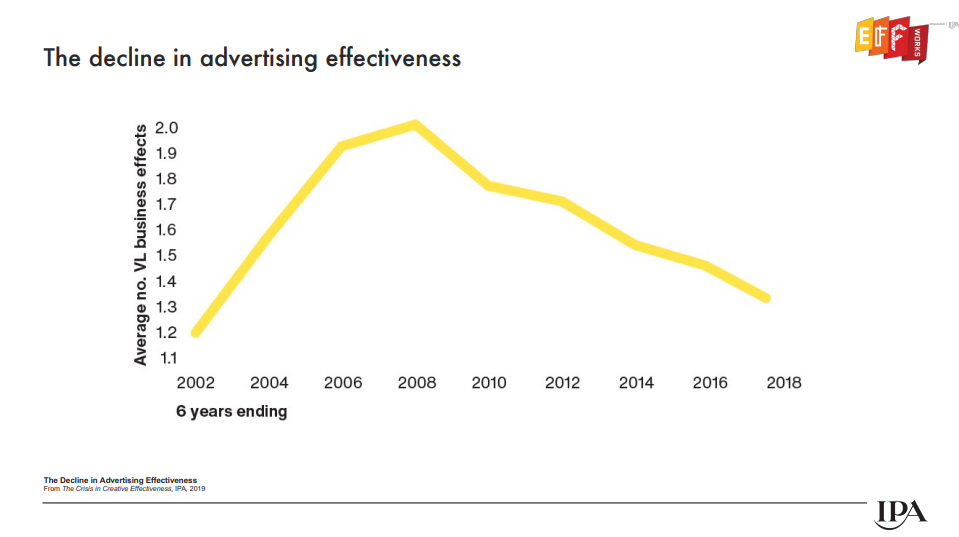

Lemon starts with Les Binet and Peter Field’s crisis in effectiveness. They argue, in their papers The Long and the Short of it and Effectiveness in Context, that there is a growing focus on short-term activations less on building long-term brand equity. Orlando Wood offers up a diagnosis and cure for this crisis in Lemon.

He stressed at the Marketing Institute event and in this paper the dangers of when one method of thinking becomes too dominant. He claimed that there’s a flatness and devitalisation of advertising, which many of us will have seen first-hand working in the industry.

System1 and Orlando Wood have done research to show the impact of creativity and emotion in advertising. They argue that ESOV (extra share of voice), which Binet and Field found to be so important, is only one half of the story and when combined with emotive /creative variables in advertising we see a much closer correlation to growth in share of market.

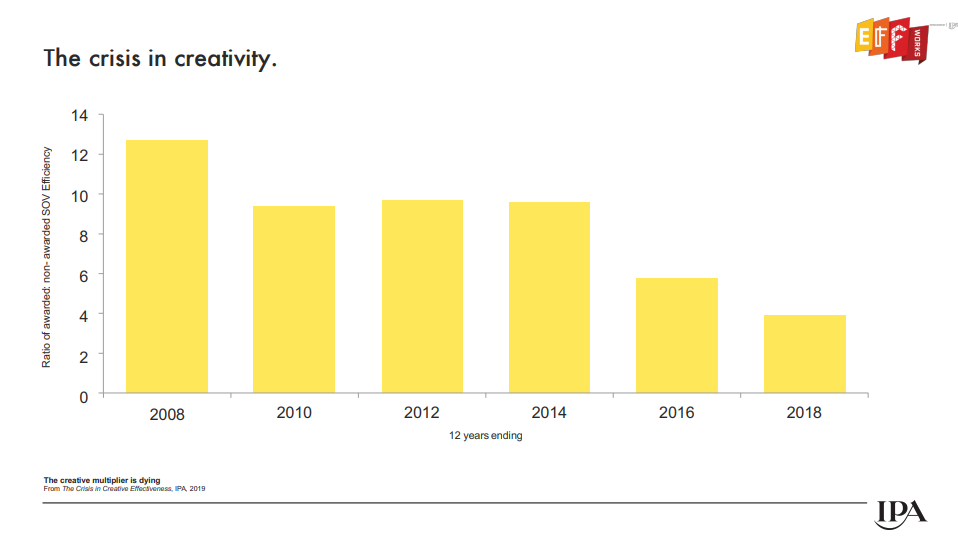

However, creativity is harder to come by these days according to research carried out by System1. The “creative modifier”, a metric measured by Wood has decreased from 12:1 to 3:1 over the last 12 years, concurrently we’ve seen a decrease in advertising effectiveness.

The divided brain

While it was originally posited that the two halves of the brain “did” different things (emotion vs logic), the more modern thinking of this is that they do things differently. This idea has been saved by the painstaking work of psychologist Iain McGilchrist in his seminal work The Master and His Emissionary. He found that this is true in humans, mammals and birds. In birds it has been observed that the left brain pecks for food and categorises seeds, insects, etc. The right brain has a broader focus and vigilantly looks for predators.

Orlando showed us the results of an experiment where doctors were able to “switch off” one half of patients brains using electrical currents. Patients were then asked to draw a picture with one half of their brain; the results show that they saw the world differently. The left-brain was more abstract and flat, the right brain drew full object and there were attempts to give depthto the pictures.

Orlando Wood broke down the characteristics of the two hemispheres as such:

|

Left Brain |

Right Brain |

|

Goal-Oriented |

Vigilant |

|

Narrow |

Broad |

|

Abraction (parts) |

Context (whole) |

|

Categories |

Empathises |

|

Explicit |

Implicit |

|

Cause and Effect |

Connections and Relationships |

|

Repeatability |

Novelty |

|

Literal, factual |

Metaphorical |

|

Self-absorbed and dogmatic |

Self-aware and questioning |

|

Language, signs and symbols |

Time, space and depth |

|

Rhythm |

Music |

Both he and McGilchirst show that hemispheric imbalance can lead to mental health issues (such as schizophrenia and anorexia nervosa) but it’s present as well in healthy people or groups. McGilchrist describes at different points in history how certain modes of thinking became dominant. The left-brain is more suppressive than right-brain and at certain points in history left-brain thinking became dominant.

Hemispheric Imbalance throughout History and Art

At the Marketing Institute event Wood began with an image from the mid-Roman period of a bust to show how left-brain thinking transformed a flourishing and creative society into a rigid system in which centralisation and standardisation are more desired. The move from mid-Roman to late-Roman period followed a move from the whole-brain/right-brain to the left-brain. The emperor Diocletian centralised, standardised and categorised everything so that if your father was a sculptor you become a sculptor. This made things easier to manage but it also led to a flatness and lack of vitality in art and architecture.

He moved onto the Renaissance period which followed the Middle Ages. Here we rediscovered perspective and each painting had a sense of time and place. The focus of the characters was on each other and there was a sense of connection. This was followed by the Reformation where this sense of perspective disappears and figures are sized based on how important they are.

During the first half of the 17th century up until the early 18th, known as the Baroque period, there was more of a focus on “pleasant sensations and feelings”. Music developed on the Renaissance idea of Polyphony with Bach, Monteverdi, Handel and others creating moving concertos of incredible depth and harmony. Architecture began to look like theatre backdrops as these two art forms melded together. Painting and sculpture re-found its sense of sensuality.

The second half of 18th century was a time of great productivity but saw a loss of creativity. Economics saw Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, James Watt perfected the steam engine. Art moved away from the minutia of details that make up the human experience and towards broader “ideas”, which are broken down and abstracted. This led to less humanist art, with less of a focus on connection and betweenness.

In the Romantic period, artists rediscover the “whole”, paintings are no longer broken into separate sections and scenes but the entire painting is one. There is greater use of dusk and dawn to show the in between times. Dreams are a large part of art and there is a feeling of yearning. This gave way to Impressionism, Pointillism, Cubism and other forms of modern art where the concept has become the thing, not the expression of it.

Popular Culture, Advertising and Effectiveness

Where high-art has eschewed a focus on the living and in-betweenness in favour of the rules, repetition and specialisation of left-brain thinking, the hemispheric balance in art has been taken up by popular culture. Here entire nations and the world gathers together around characters and stories, we connect with fictional settings as if they were our homes. This in-betweenness even gave birth to a demographic in the teenager. Music, film and television were created to focus on this bracket, who were no longer children, but not quite adults.

Recently, we have become more of a left-brain-dominant society as shown by our popular culture. Music lyrics are becoming more repetitive as shown in a study by Colin Morris, which is expanded upon in Lemon. From 1980-2001 the average number of franchise movies in the top 10 highest grossing films of the year was 2.2. Since then, the average number has gone up to 5.7, showing an increase in repetition in our film choices.

This is also shown in television choices as we moved towards talent shows and formatted reality TV as well as sport, and away from sitcoms and soaps, in the top 10 most viewed programmes of the year.

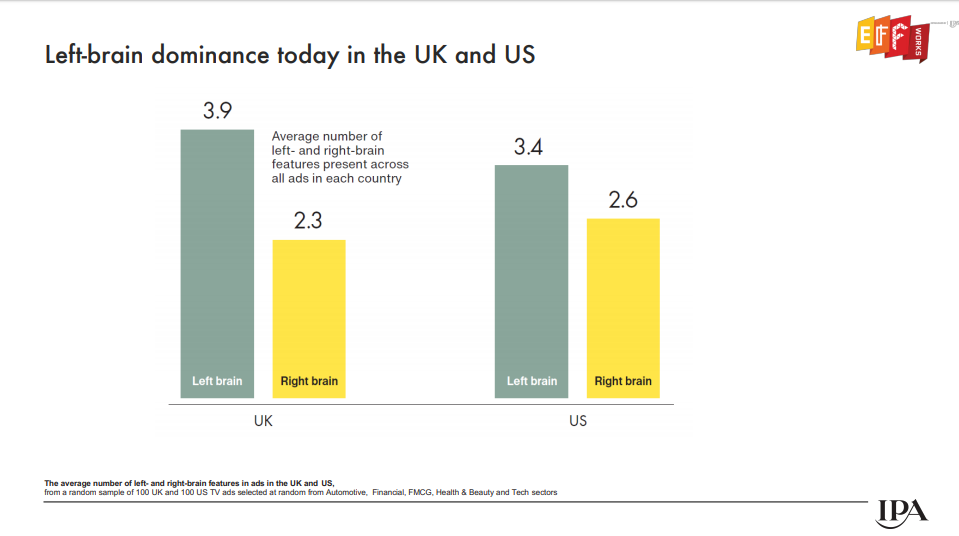

We’ve moved from right brain to left in advertising, with less connection, less sense of place and time and more abstract ads. We need to activate the right brain in advertising as this hemisphere looks out for things that a novel and new, it has a broader view and looks at things in context which is vital.

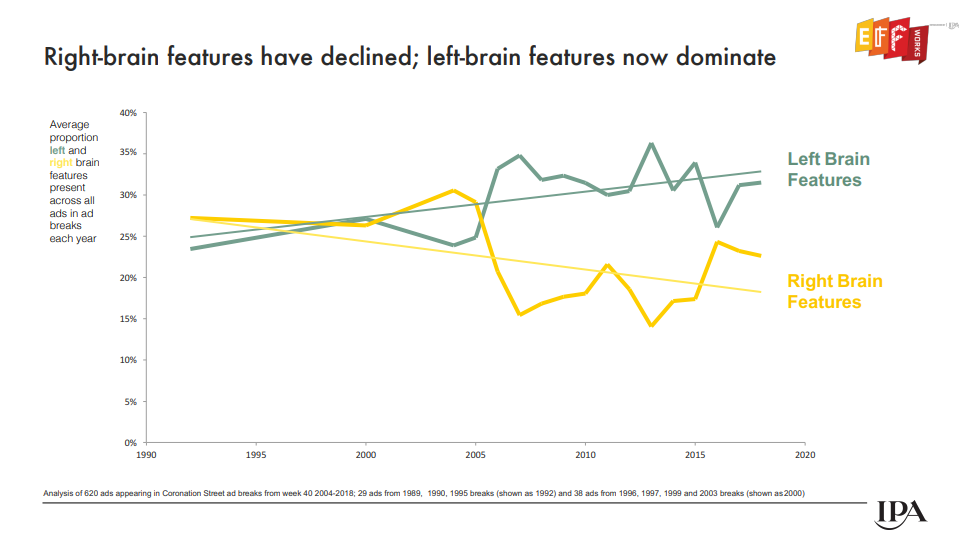

System1 took ad breaks from Coronation Street, which they are able to recreate from Nielsen data going back to 2004, to compare how the average unremarkable ad break has changed in the last 16 years. They used aggregated data back to 1992 to go further back and view the changes in ad breaks for the last 28 years.

They measured these breaks across a number of parameters. Right-brain include implicit communication, cultural references, the playing out of scenes and more; and left-brain features include rhythmic soundtrack, voiceover and text obtruding on the ad. They found that since 1992 right-brain features have diminished in advertising while the use of left-brain features has risen. He gave two examples of how advertising has changed in the past couple of decades from one enamoured with characters, scenes and betweenness to one that prizes abstraction, overt messages and solitude.

An example of right-brain-thinking can be found in this Heineken Ad from 1985. This show connectedness, cultural parody, characters and other traits associated with the right-brain.

The opposite can be found in this GoDaddy Ad from 2018, which exhibits all the features of left-brain-thinking. These include: text overlay, rhythmic soundtrack, people alone in the frame and general abstraction with no story or characters.

In art, these differences might not matter, but advertising serves a commercial purpose so we need to measure the commercial impact of this switch from right-brain to left-brain thinking. System1’s analysis has shown that ads with more right-brain features perform better than those with more left-brain features when it comes to advertising effectiveness.

The change from right-brained to left-brained advertising is matched to a fall in effectiveness. This fall in effectiveness maps a decreased used in TV advertising also, as more brands go online and focus on short-term activation rather than long term brand-building.

This change has also had an effect on advertising’s reputation. The period from 1992 to the present has seen a precipitous drop in favourability towards the advertising industry. As Rory Hamilton of Boys and Girls put it at Plannervision, we seem to have forgotten the contract with our audience: they listen to our brand message for a little bit of entertainment. The left-brain believes that the brand message is important in itself, whereas the right-brain understands this contract better.

According to David Trott, 90% of advertising is ignored. What can a brand do to be in the 10%? A lie that we’ve been told as an industry is that attention spans are getting shorter. This simply is not true, the average length of time spent on Netflix is 71min on Youtube 34mins is the average. People are paying attention, but they’re paying attention to content that they enjoy, not advertising messages that are being forced upon them with no entertainment value. People don’t trust advertising anymore, trust in the industry has dropped by 60% in last 30 years. By adopting the thinking in Lemon we can fight this fall.

The Changing Agency Model

Orlando states that the left-brain likes to encroach on the right-brain, and seeks control. The left-brain likes to break things into smaller pieces which has changed the agency model for the worse. No longer are agencies paid a commission of the overall media spend, creative is now broken out and they are paid retainer fees which are billed hourly. As a result, agencies have less time to crack briefs and the work is divided among teams leading to a poorer quality of work produced. The squeeze on costs means less actors, sets and scenes which are all right-brain traits. Graphics and voiceover have become more common, which are left-brain features in advertising.

As agencies become part of larger holding companies they have two masters, the client and the shareholder. The shareholder-focus has increased workloads and reduced staff-costs leading to a workforce that must churn out work. This leaves little time for the difficult and unpredictable task of creativity. As well as this there has been an expansion in the type of work done by agencies. This has led to the creation of a multitude of teams and departments which compartmentalizes work and doesn’t allow for the broad, context driven, right-brain thinking that produces effective work.

The left-brain likes standardisation which has led to more global ads. These ads are difficult to attach to a time/place, have generic characters and any sense of betweenness is lost. Localised ads are more effective but cannot be standardised due to cultural specificities from region to region.

More and more budgets have moved to digital media, especially social media and PPC campaigns. Digital guidelines favour left-brain features. They tend to feature abstraction, repetition and visual rhythm. As Orlando Wood puts it in Lemon, “With Companies increasingly designing for mobile first, before considering TV or other channels, these guidelines are harmful to the long-term growth prospects of brands operating across channels.

Solutions

As a solution to the current creative malaise that is affecting the advertising industry, Orlando puts forward a few suggestions.

Firstly, it’s important that briefs are geared toward the right brain. The creative brief needs to be liberating. The right brain understands things as a whole and as they are, the left brain takes things in pieces and tries to represent them. Creative briefs should be narratives or conversations where creatives can listen for the little “burrs” as SArah CArter would call them (phrases, idioms, metaphors, etc. that stick with us), from here an agency will be able to create a campaign that sticks in the right-brain of customers. When one has this, be sure not to abstract it or break it down, instead build on it and add depth to the picture.

He also suggests that we need to move away from the rigidity that left-brain thinking has gotten us into. Rather than treating the brief or the script as sacrosanct, it should be treated as a springboard from which great directors, actors and happy accidents can contribute to creating a memorable and beloved ad campaign. He cites the Dulux dog, the Smash Martians and other seminal ads when stating that the best parts of some campaigns were never planned for. He states that we should use research judiciously, that research “is data, not a decision”.

He also looked for the right-brained to be more confident in their creations. More often than not, the creative side of a business will have to justify itself to the more logical side. When it comes to advertising this research has shown that there is greater value in creative work so the attitude shouldn’t be “we can’t afford to be creative or take chances” it should be “If we don’t act creatively we won’t be successful, we can’t afford to not take chances”.

He equates the modern trend of “Disruption” with the punk movement. An attempt to jolt conventional thinking without putting anything in its place – creating a void but failing to fill it. In the attempt to “shock” the mainstream and earn media instead of paying for it a brand will gain attention without entertaining the audience. He claims that this will not lead to long-term brand building as desired but instead lead to a short-term effect.

This work expands on the work of the Ehrenberg-Bass institute which stressed the importance of distinctive assets (logos, fonts, shapes, colours, etc.). System1 claim that there are two key assets which prioritise the living and allow brands to create a “fluent device” which can grow creativity for the long-term. These are characters (such as the Honey Monster or Comparethemarket’s Meerkats) and scenario, or slogan, (such as “you should’ve gone to Specsavers”). These lessen the cognitive load on an audience and make them more favourable to ad campaigns. System1, in their research of over 330 campaigns from 1999 onwards, found that campaigns with these fluent devices are much more likely to achieve market share growth and profit gain than campaigns without.

The number of brands using a fluent device, especially a character, has decreased in recent years, due in part to the over-reliance on digital media. The first few years of social media advertising there was an aversion to anything that looked like advertising as it was believed that advertising was not welcome in this space. The work of Orlando Wood has shown that “native content” doesn’t perform as well as standard advertising which uses these fluent devices. This antipathy to fluent devices is unusual as memes are the lingua franca of the internet and the creation of

Conclusion

The thinking in this piece of work is cogent and Orlando Wood makes lots of excellent points that can be seen looking back through history as well as in our current context. By framing his argument in the areas of psychology, neurology and art history he has given us a wider context in which to think of advertising, which is a very right-brained move all told. He finishes the paper with practical solutions for this crisis, grounding the theory in real applicable tools.

Should the media industry follow his suggestions and listen to the advice in this research, we could see a new golden age of advertising. This age wouldn’t be based on disruption or innovation but on honest human connection. This paper seems to suggest that our brains haven’t changed that much since the mid-Roman period, we’ve just tricked ourselves into thinking we have.